Introduction: Executive Framing: Why This Matters Now

The automotive supply chain is undergoing a structural reset. What once functioned as a predictable, tiered system optimized for cost, scale, and execution is being reshaped by forces that fundamentally alter how value is created and captured. This is not another cyclical disruption. It is a permanent shift in expectations.

For many suppliers, the instinct is to focus on visible pressures - electrification, pricing erosion, regulatory burden, geopolitical volatility. These are real challenges, but they are not the most dangerous ones. The greatest risk facing Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers today is far more existential: irrelevance.

As vehicles become electrified, software-defined, and regulation-heavy, OEMs are no longer looking for vendors who simply manufacture to specification. They need partners who can think alongside them, partners who understand systems, contribute early to design and architecture decisions, and help navigate complexity across technology, regulation, and time-to-market.

In this environment, tier status is losing its strategic meaning. Being a Tier 1 or Tier 2 supplier no longer guarantees proximity to decision-making or long-term relevance. What matters instead is the ability to create value beyond parts and price.

The automotive industry is quietly moving away from hierarchical supply chains toward ecosystems of collaboration. Transactional relationships are giving way to strategic partnerships. Execution alone is no longer enough; influence, insight, and shared accountability are becoming the new currencies of relevance.

This shift elevates the conversation from procurement to the C-suite. It forces a fundamental question for automotive leaders:

Will your organization continue to compete for orders or will it evolve into a partner that OEMs rely on when complexity increases?

The answer to that question will determine not just who grows, but who survives in the next decade of automotive transformation.

The Old World: How the Tiered Supply Chain Was Built

For decades, the automotive industry operated on a clearly defined and highly effective tiered supply chain model. This structure was not accidental; it was deliberately designed to support scale, predictability, and cost efficiency in an industry defined by capital intensity and long product lifecycles.

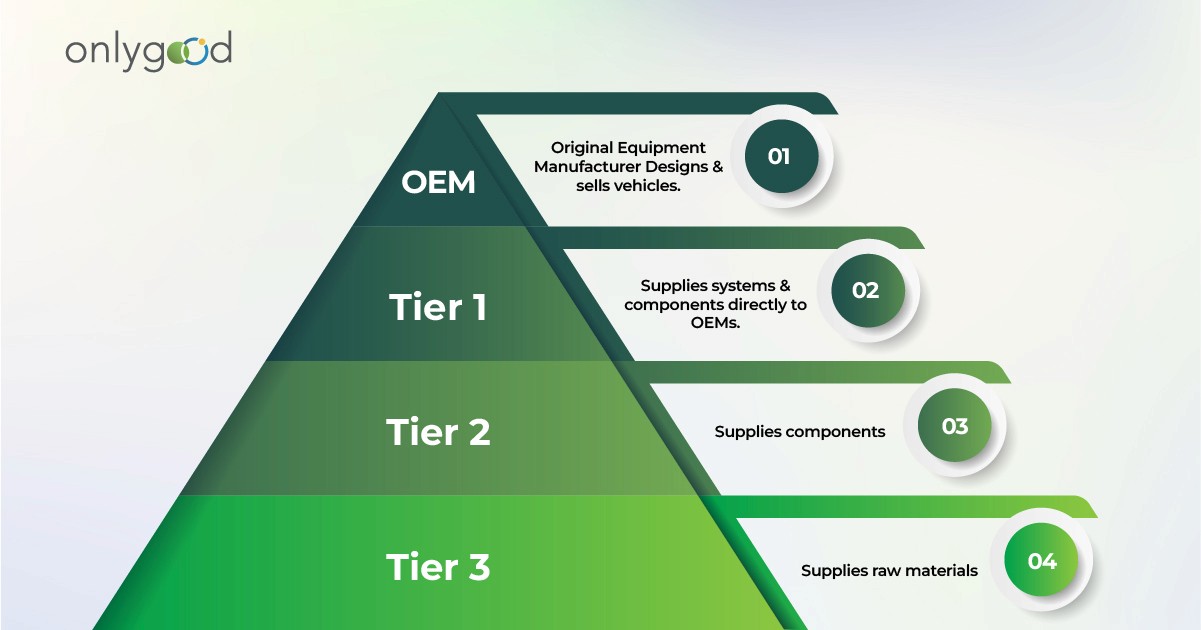

At its core sat a simple pyramid.

OEMs owned vehicle architecture, brand, and final assembly. They defined platforms, managed product portfolios, and orchestrated the overall ecosystem. Tier 1 suppliers delivered complete systems and modules, powertrain components, interiors, electronics, and chassis assemblies integrated directly into vehicle platforms. Tier 2 suppliers supported Tier 1s with components, sub-assemblies, raw materials, and specialized manufacturing capabilities.

This hierarchy created clear boundaries of responsibility and accountability. Each tier knew its role. Information flowed downward through specifications; execution flowed upward through parts and systems. Commercial relationships were largely transactional, governed by cost, quality, and delivery performance.

The model worked exceptionally well because it was aligned with the realities of its time.

Vehicle platforms were stable, often lasting a decade or more with limited architectural change. Development cycles were long and predictable, allowing suppliers to optimize tooling, capacity, and processes over extended horizons. Cost efficiency was paramount, and scale was the primary lever for competitiveness. In this environment, success depended on flawless execution rather than continuous reinvention.

As a result, the tiered supply chain became highly optimized for manufacturing excellence. It rewarded reliability, process discipline, and the ability to deliver at scale. Innovation existed, but it was largely incremental and bounded by pre-defined specifications rather than open-ended collaboration.

What this system did not prioritize and did not need to prioritize at the time was co-creation. Suppliers were not expected to influence system architecture, challenge design assumptions, or align long-term technology roadmaps with OEM strategy. Their value was measured by how well they executed what had already been decided.

For much of automotive history, this was not a limitation. It was a strength.

The tiered pyramid enabled one of the most complex industrial ecosystems ever built, delivering millions of vehicles with remarkable consistency, quality, and cost control across global markets.

The Break in the System: Why the Model Is Failing

The traditional tiered supply chain was built for stability. Today, the automotive industry is defined by complexity.

Over the past decade, a convergence of forces has fundamentally altered how vehicles are designed, developed, and delivered. Electrification has restructured powertrain architectures. Software-defined vehicles have shifted value from mechanical systems to code, electronics, and integration. ESG and regulatory mandates now influence everything from material selection to supplier geography. Development timelines have compressed, while global supply volatility has become a persistent condition rather than an exception.

Each of these forces alone would strain a rigid, transactional supply chain. Together, they overwhelm it.

The tiered model struggles not because suppliers lack capability, but because the structure itself was never designed to absorb this level of interdependence. Specifications can no longer be frozen early. Design trade-offs must be made continuously across hardware, software, sustainability, and cost. Decisions taken in one part of the system increasingly ripple across the entire vehicle architecture.

In this environment, transactional relationships collapse under their own weight. Build-to-print execution assumes clarity and stability. Complexity demands collaboration and iteration. When uncertainty increases, rigid handoffs become bottlenecks. Late-stage supplier engagement leads to rework, delays, and suboptimal outcomes—precisely when speed and integration matter most.

OEMs are responding by rethinking how they engage with their supply base.

They are pulling select suppliers closer into the early stages of concept development, architecture definition, and platform planning. Not to outsource responsibility, but to share it. Not to increase dependency, but to reduce risk.

Today, OEMs increasingly require:

Early engineering input to shape design decisions before they are locked in

System-level thinking that considers interactions across components, software, and sustainability requirements

Long-term platform alignment that ensures supplier investments evolve alongside OEM roadmaps

This is not a shift in preference. It is a shift in necessity.

OEMs are not pulling suppliers closer because it is fashionable. They are doing it because the old model cannot absorb complexity.

The breaking point is already visible. Suppliers who engage late are relegated to execution roles with shrinking influence and margin pressure. Those who engage early gain context, relevance, and staying power.

The question is no longer whether the system will change. It already has. The real question is which suppliers will adapt their role within it and which will be left optimizing for a model that no longer exists.

Why “Tier 0.5” Is the Wrong Language

As OEM–supplier relationships evolve, industry conversations have begun to use the term “Tier 0.5” to describe suppliers operating closer to OEMs than traditional Tier 1s. The phrase is often used to signal early involvement, deeper collaboration, or proximity to decision-making.

While the term is convenient, it is ultimately misleading.

“Tier 0.5” attempts to explain where a supplier sits in the value chain but not what that supplier actually contributes. It is a positional label in a moment that demands a strategic one.

The language itself remains rooted in the old hierarchy. It implies a rearrangement of layers rather than a redefinition of roles. By anchoring the conversation to tiers, it reinforces the very framework that is breaking down under complexity.

More importantly, “Tier 0.5” fails to capture the nature of the responsibility OEMs are now asking select suppliers to assume. Early engagement alone does not make a supplier strategic. Physical proximity to OEM teams does not equate to influence. Being closer in the chain does not guarantee relevance.

What matters is not position but contribution.

This is why a more accurate and useful construct is C-Suite Partner (C-SP).

A C-Suite Partner is not defined by tier placement or sourcing category. It is defined by the depth of collaboration, the scope of responsibility, and the level at which decisions are made. These partners engage directly with OEM leadership, R&D, and program teams to shape architecture, co-develop systems, and align long-term roadmaps.

They move beyond execution into problem definition. Beyond cost negotiation into shared risk and reward. Beyond transactions into strategic continuity.

The real shift is not about where a supplier sits but how value is created.

By reframing the conversation in these terms, the industry moves away from incremental labels and toward a clearer understanding of the future: one where relevance is earned through contribution, trust, and long-term alignment not proximity in a fading hierarchy.

Defining the C-Suite Partner

The term C-Suite Partner (C-SP) describes a fundamentally different supplier archetype, one defined not by tier placement, but by strategic responsibility and depth of engagement.

What a C-Suite Partner Is:

A C-Suite Partner engages early and directly with OEM leadership, R&D, and core program teams often before specifications are finalized and sourcing decisions are locked.

Their role extends beyond execution into shaping outcomes.

C-Suite Partners actively participate in:

Vehicle and system architecture decisions, not just component design

System-level trade-offs, balancing performance, cost, manufacturability, sustainability, and risk

Technology roadmap planning, aligned with the OEM’s long-term platform vision

Rather than reacting to finalized requirements, they help define the problem and co-create the solution.

Critically, C-Suite Partners align their own investments in engineering talent, capital expenditure, digital capabilities, and process innovation with multi-year vehicle platforms, not short-term sourcing cycles.

Commercially, they move away from build-to-print pricing models and toward shared risk–reward structures, platform-level engagements, and long-term commitments that reflect mutual dependence and trust.

This is not closeness by proximity. It is closeness by responsibility.

What a C-Suite Partner Is Not

A C-Suite Partner is not defined by:

Tier position (Tier 1, Tier 2, or any hybrid label)

A “preferred vendor” or strategic supplier badge

Transactional execution against fixed specifications

They are not optimized only for cost, capacity, or delivery metrics in isolation.

Execution excellence is expected but it is no longer sufficient.

The Litmus Test

If your organization is:

Engaged after specifications are frozen

Measured primarily on price and delivery

Investing only against current programs, not future platforms

Then you are still operating in a traditional supplier role regardless of tier.

If you are:

In the room during concept and architecture discussions

Asked to help navigate trade-offs and uncertainty

Aligning your roadmap with the OEM’s long-term vision

Then you are already on the path to becoming a C-Suite Partner.

This distinction matters because in the next phase of the automotive industry, relevance will not be granted by tier.

It will be earned through partnership.

Proof from History: The Japanese Automotive Value System

The idea of C-Suite Partnership is often presented as a response to modern complexity.

In reality, it is a proven operating model—one that has delivered durable advantage for decades.

The clearest evidence comes from the Japanese automotive ecosystem, led by companies such as Toyota Motor Corporation and Suzuki Motor Corporation.

These OEMs did not build global competitiveness by treating suppliers as interchangeable vendors. They built it by cultivating deep, long-term partnerships anchored in shared responsibility and continuous capability building.

The Operating Principles Behind the System

The Japanese value system is commonly associated with operational practices such as:

Just-In-Time (JIT) production to eliminate waste and expose inefficiencies

Kanban-based material flow to synchronize demand and supply

Kaizen as a continuous, organization-wide improvement discipline

5S to institutionalize quality, safety, and process rigor

These practices, however, were not merely factory tools.

They were relationship systems.

JIT cannot function without trust.

Kanban collapses without transparency.

Kaizen fails without long-term commitment.

5S erodes without shared ownership.

Trust as Infrastructure, Not Sentiment

Japanese OEMs encouraged suppliers to:

Invest in engineering depth

Improve processes continuously

Build specialized capabilities over time

They did so by offering something rare in global manufacturing: predictability and patience.

Suppliers were not optimized for short-term price reductions, but for long-term performance improvement. In return, OEMs gained:

Faster problem resolution

Higher quality and reliability

Deep system knowledge embedded across the supply base

This mutual dependence created shared accountability, where success and failure were collectively owned—not contractually outsourced.

Why the System Proved Resilient Under Crisis

The true strength of this ecosystem became most visible during periods of disruption—natural disasters, supply shocks, and demand volatility.

When crises occurred:

Information flowed quickly across OEM and supplier networks

Engineering teams collaborated in real time to redesign, re-source, or rebalance

Recovery was collective, not adversarial

Because relationships were built on trust and long-term alignment, the system absorbed shocks that would have fractured transactional supply chains.

Resilience was not accidental. It was designed.

The Enduring Insight

The Japanese automotive value system demonstrates a critical truth:

Strategic collaboration is not a modern innovation, it is a disciplined tradition.

What is new today is not the concept of deep partnership.

What is new is the scale of complexity that now makes this model unavoidable.

The future is not inventing something radical.

It is returning deliberately to what has already been proven to work.

Collaboration Is a Process, Not an Event

One of the most damaging misconceptions in the automotive supply chain is the belief that partnership can be accelerated through contracts, labels, or organizational announcements.

It cannot.

Real collaboration takes time typically 18 to 24 months to mature. Not because organizations are slow, but because the foundations of partnership cannot be compressed.

Why Time Is Non-Negotiable

Three elements must evolve in parallel before true collaboration emerges:

1. Trust:

Trust is not declared. It is earned through repeated delivery, transparency during setbacks, and consistency under pressure. OEMs must see how a supplier behaves when specifications change, timelines compress, or costs escalate.

2. Engineering Rhythm:

Effective collaboration requires synchronized development cycles, shared problem-solving language, and aligned decision-making tempo. This rhythm only forms after teams work together across multiple iterations not during a single program.

3. Governance Maturity:

C-Suite Partnerships demand escalation paths, decision rights, and accountability structures that operate beyond procurement. These governance mechanisms take time to design, test, and stabilize across organizations.

None of this can be rushed without eroding credibility.

What Each Side Must Commit To

For collaboration to mature, both suppliers and OEMs must invest ahead of visible returns.

Suppliers must:

Invest in engineering depth and systems capability before revenue is guaranteed

Allocate senior leadership attention to OEM relationships

Demonstrate value repeatedly, not just during sourcing cycles

OEMs must:

Engage suppliers earlier in concept and architecture discussions

Allow meaningful influence before specifications are frozen

Shift from transactional oversight to joint decision-making

Partnership fails when either side waits for proof before committing.

Earned, Not Granted: What Leading Suppliers Show Us

Global suppliers such as Bosch, Valeo, and Samvardhana Motherson International are often cited as examples of deep OEM integration.

They are not exceptions. They are case studies in patience.

Each earned their position through:

Early engineering involvement

Co-location of development teams

Long-term participation in vehicle platforms rather than isolated projects

Their proximity to OEM leadership was not awarded. It was built over years of disciplined execution and alignment.

The Strategic Reframe

Collaboration is not an acceleration strategy. It is a compounding strategy.

Organizations willing to invest time, capability, and trust upfront create relationships that outperform through cycles while others remain trapped in perpetual re-sourcing and margin erosion.

The question is not how fast partnership can begin. It is whether leadership is prepared to stay the course long enough for it to matter.

Why the ROI Is Structural (Not Tactical)

For CFOs and CEOs, the question is not whether collaboration is philosophically appealing. It is whether it produces durable financial and strategic returns.

C-Suite Partnership does but not in the way most sourcing models measure ROI.

Revenue Predictability Over Margin Volatility

Transactional suppliers optimize for program-level margins. C-Suite Partners optimize for platform continuity.

By embedding deeper into OEM roadmaps, these partners are retained across cycles, refreshes, and derivatives. This results in:

More predictable revenue streams

Lower exposure to abrupt re-sourcing events

Reduced volatility during demand corrections

Predictability becomes a strategic asset especially in capital-intensive engineering environments.

Higher Returns on Engineering Capital

Engineering investments are expensive and often underutilized in transactional models, where learnings reset with each RFQ.

C-Suite Partners amortize engineering effort across:

Multi-year platforms

Multiple vehicle variants

Successive technology generations

This dramatically improves return on invested engineering capital, not by raising prices, but by extending relevance.

Platform Continuity, Not Project Churn

When suppliers are involved early and continuously, they move from executing projects to shaping platforms.

This continuity reduces:

Re-engineering waste

Late-stage design changes

Cost overruns driven by misalignment

Platforms become more stable. Suppliers become harder to replace.

Structural Protection During Downturns

When cycles turn, OEMs reduce risk not partners.

C-Suite Partners are:

Retained in core programs

Involved in recovery planning

Engaged earlier in next-generation platforms

Others compete for shrinking RFQs.

This is not preferential treatment. It is risk management.

Early Access to the Future

The most valuable benefit is not margin; it is timing.

C-Suite Partners gain:

Earlier visibility into future architectures

Influence over technology direction

More time to align investments

By the time sourcing opens, they are already embedded.

C-Suite Partnership is not about higher margins. It is about staying relevant when cycles turn.

What Tier 1 & Tier 2 Suppliers Must Do Now

Aspiring to C-Suite Partnership requires a deliberate shift not incremental improvement.

There are four non-negotiable changes.

1. Build Engineering Depth and Systems Thinking

Component excellence is no longer enough.

Suppliers must understand:

System interactions

Architecture trade-offs

Integration consequences across the vehicle

Without systems literacy, early engagement is impossible.

2. Engage Earlier Before Specifications Exist

Waiting for finalized requirements signals execution, not leadership.

Suppliers must:

Contribute to problem definition

Offer design alternatives

Engage before cost is fixed

Influence begins before drawings are released.

3. Align Commercial Models to Platforms, Not Projects

Annual sourcing cycles destroy long-term value.

C-Suite Partners shift toward:

Shared risk–reward structures

Multi-year commitments

Platform-aligned economics

Short-term pricing optimization is replaced by long-term relevance.

4. Govern OEM Relationships at the Leadership Level

Strategic partnerships cannot be delegated.

OEM relationships must be:

Owned by senior leadership

Reviewed with long-term intent

Protected from short-term erosion

If leadership treats the relationship as tactical, the OEM will too.

The Future State: From Pyramids to Value Ecosystems

The automotive industry is moving away from rigid pyramids.

In their place, value ecosystems are emerging.

These ecosystems are defined not by hierarchy, but by contribution.

What Will Define Competitive Advantage

In the next decade, advantage will not come from:

Scale alone

Cost optimization alone

Manufacturing efficiency alone

It will come from:

The ability to collaborate across complexity

The discipline to invest ahead of immediate returns

The patience to build trust before monetization

Endurance will matter more than speed.

Who Will Shape the Industry

C-Suite Partners will not chase RFQs.

They will:

Shape platforms

Influence architectures

Co-create roadmaps

Others will remain reactive optimized for execution, but excluded from strategy.

Conclusion

The automotive industry is entering a decade of complexity, not stability.

In that environment:

“In the next decade, OEMs will not remember who was cheapest.

They will remember who stood with them when complexity increased.”

Or more simply:

The difference between being sourced and being trusted is the difference between surviving and leading.

The question for every supplier leadership team is no longer whether this shift is happening.

It is whether you are positioned inside it or outside looking in.